Class XII - Chapter -5 (Flamingo)-Indigo by Louis Fischer

Class 12 English Chapter 5 - Indigo

by Louis Fischer

About the Author

Louis Fischer (1896-1970) was born in Philadelphia in 1896. He served as a volunteer in the British Army between 1918-1920. Fischer made a career as a journalist and wrote for The New York Times, The Saturday Review and for European and Asian publications. He was also a member of the faculty of Princeton University.Louis Fischer (1896–1970) was an American journalist, political historian, and biographer. Here’s a snapshot of his life and works:

📚 Early Life & Career

• Born in Philadelphia on 29 February 1896, Fischer was the son of Orthodox Jewish immigrants. His father worked as a fish peddler.

• He studied at the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy (1914–16), then taught school before volunteering for the British Army around 1918–1920

🌍 Journalism & Political Engagement

• Fischer became a foreign correspondent, living in the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1936. He reported on Russian politics and international affairs

• In 1933, his pro-Communist writings were burned by the Nazis

• He participated in the Spanish Civil War and later worked with The Nation and other prominent publications.

✍️ Major Works & Recognitions

• Oil Imperialism (1926), The Soviets in World Affairs (1930), Men and Politics (his autobiography, 1941)

• Authored The Life of Mahatma Gandhi (1950), which inspired the acclaimed 1982 film Gandhi

• Wrote a biography of Lenin, earning the 1965 National Book Award in History & Biography

🎓 Academic Positions

• Joined the Institute for Advanced Study and later served as Visiting Lecturer at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School (1958–1970) ().

🇮🇳 Time in India

• Visited Gandhi at Sevagram Ashram in May–June 1942, spending around a week in his company

Introduction

The story is based on the interview taken by Louis Fischer of Mahatma Gandhi. In order to write on him he had visited him in 1942 at his ashram- Sevagram where he was told about the Indigo Movement started by Gandhiji. The story revolves around the struggle of Gandhi and other prominent leaders in order to safeguard sharecroppers from the atrocities of landlords.The theme of the chapter “Indigo” by Louis Fischer, from Class XII NCERT English (Flamingo), revolves around the struggle for justice and the emergence of Mahatma Gandhi as a leader of national importance. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

🌿 Central Theme:

Social and political awakening through non-violent resistance.

🧩 Key Sub-themes:

1. Struggle Against Injustice:

• The peasants of Champaran were exploited by British planters through the indigo sharecropping system.

• Gandhi’s intervention marked a turning point in their resistance against oppression.

2. Role of Civil Disobedience:

• Gandhi used non-violent protest and civil disobedience as tools.

• His refusal to obey an unjust order from the British authorities was a powerful message of resistance.

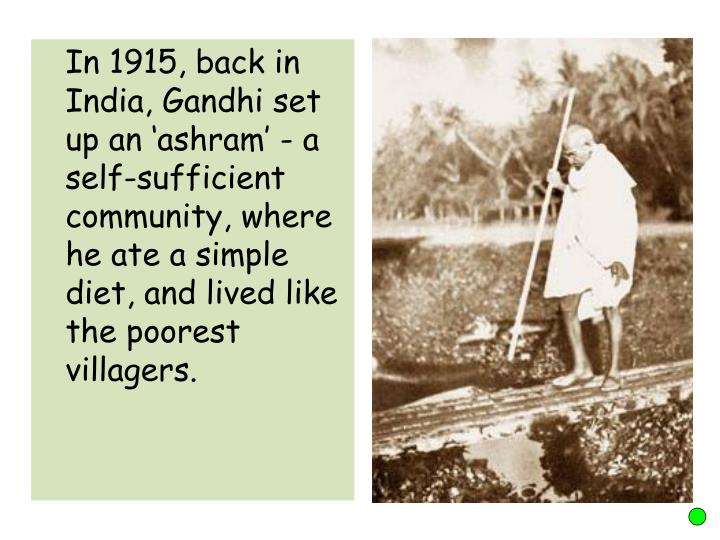

3. Empowerment Through Self-Reliance:

• Gandhi encouraged peasants to stand up for their rights.

• He also emphasized education, hygiene, and social upliftment, showing a holistic approach to freedom.

4. Leadership and Nationalism:

• The Champaran episode marked Gandhi’s first major involvement in an Indian mass struggle.

• It transformed him from a political figure into a mass leader with deep grassroots support.

Characters and their character sketches

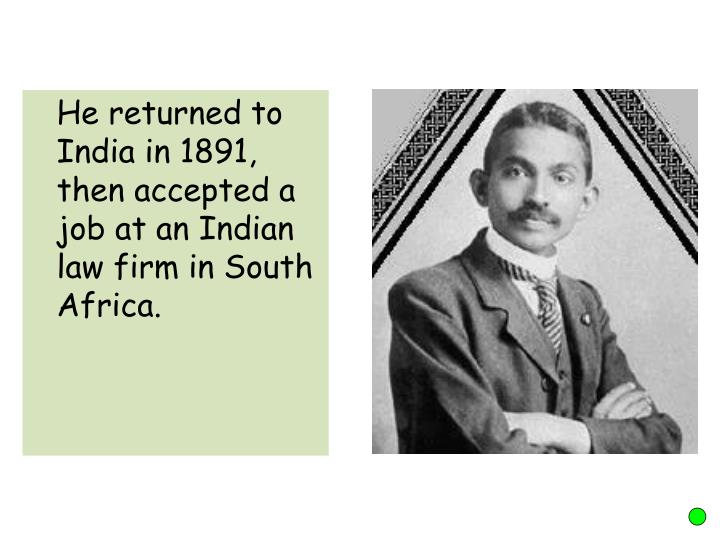

🧑🦲 1. Mahatma Gandhi

Role: Protagonist; Leader of the Champaran movement

Character Sketch:

• Compassionate and empathetic: Gandhi was deeply moved by the sufferings of the poor indigo farmers.

• Determined and courageous: He defied British authorities by refusing to leave Champaran, ready to face imprisonment.

• Practical and strategic: Instead of aggressive protest, he used non-violence, truth (Satyagraha), and civil disobedience to bring about change.

• Inspiring leader: He united peasants, inspired lawyers, and motivated others to fight for justice.

• Holistic thinker: Gandhi didn’t just fight for economic justice; he also worked for the villagers’ education, hygiene, and self-reliance.

📌 Conclusion: Gandhi’s role in Champaran marked the birth of India’s civil disobedience movement and established him as a national leader.

🧔♂️ 2. Rajkumar Shukla

Role: Poor peasant from Champaran; catalyst for the story

Character Sketch:

• Determined and persistent: Despite his poverty and illiteracy, he followed Gandhi everywhere until he agreed to visit Champaran.

• Symbol of suffering peasants: Shukla represents the countless exploited indigo sharecroppers.

• Simple but brave: He had the courage to approach and persuade a national leader for help.

📌 Conclusion: Shukla’s unwavering efforts led to the beginning of a historic movement in India’s freedom struggle.

⚖️ 3. British Planters

Role: Oppressors of the Champaran peasants

Character Sketch:

• Exploitative and unjust: Forced peasants to grow indigo on 15% of their land and took advantage of them through unfair agreements.

• Cowardly when challenged: Backed off once Gandhi legally confronted them.

• Symbol of colonial oppression.

📌 Conclusion: Represent the exploitative policies of the British Raj and their eventual retreat in the face of united, peaceful resistance.

👨⚖️ 4. Local Lawyers of Bihar

Role: Supporters of Gandhi during the Champaran episode

Character Sketch:

• Initially hesitant: At first, they didn’t want to defy the British authorities.

• Inspired by Gandhi: His courage made them realize their duty to support justice.

• Supportive and united: They stood with Gandhi, offering legal help and solidarity.

📌 Conclusion: Reflect the awakening of Indian intellectuals and professionals in the freedom struggle.

👨🏫 5. Government Officials and British Authorities

Role: Tried to suppress Gandhi’s activities

Character Sketch:

• Authoritative and rigid: Ordered Gandhi to leave Champaran.

• Reluctant to punish him: Feared public opinion and Gandhi’s growing influence.

• Eventually gave in: Allowed Gandhi to investigate and resolve the issue.

📌 Conclusion: Their response shows the power of non-violent protest and the shift in colonial authority’s attitude.

Indigo- Summary

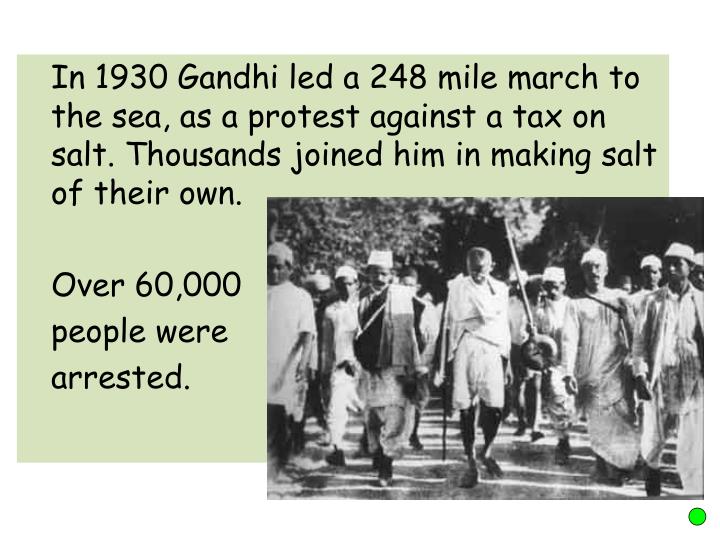

Louis Fischer met Gandhi in 1942 at his ashram in Sevagram. Gandhi told him that how he initiated the departure of the British from India. He recalled that it in 1917 at the request of Rajkumar Shukla, a sharecropper from Champaran, he visited the place. Gandhi had gone to Lucknow to attend the annual meeting of Indian National Congress in the year 1916. Shukla told him that he had come from Champaran to seek his help in order to safeguard the interests of the sharecroppers. Gandhi told him that he was busy so Shukla accompanied him to various places till he consented to visit Chaparan. His firm decision impressed Gandhiji and he promised him that he would visit Calcutta at a particular date and then Shukla could come and take him along to Champaran. Shukla met him at Calcutta and they took a train to Patna. Gandhi went to lawyer Rajendra Prasad’s house and they waited for him. In order to grab complete knowledge of the situation, he reached Muzzafarpur on 15th April 1917. He was welcomed by Prof. J.B Kriplani and his students. Gandhi was surprised to see the immense support for an advocate of home rule like him. He also met some lawyers who were already handling cases of sharecroppers. As per the contract, 15 percent of the peasant’s land holding was to be reserved for cultivation of indigo, the crop of which was given to the landlord as rent. This system was very oppressive. Gandhi wanted to help the sharecroppers. So he visited the British landlord association but he was not given any information because he was an outsider. He then went to the commissioner of Tirhut division who threatened Gandhi and ask him to leave Tirhut. Instead of returning, he went to Motihari. Here he started gathering complete information about the indigo contract. He was accompanied by many lawyers. One day as he was on his way to meet a peasant, who was maltreated by the indigo planters, he was stopped by the police superintendent’s messenger who served him a notice asking him to leave. Gandhi received the notice but disobeyed the order. A case was filed against him. Many lawyers came to advise him but when he stressed, they all joined his struggle and even consented to go to jail in order to help the poor peasants. On the day of trial, a large crowd gathered near the court. It became impossible to handle them. Gandhi helped the officers to control the crowd. Gandhi gave his statement that he was not a lawbreaker but he disobeyed so that he could help the peasants. He was granted bail and later on, the case against him was dropped. Gandhi and his associates started gathering all sorts of information related to the indigo contract and its misuse. Later, a commission was set up to look into the matter. After the inquiry was conducted, the planters were found guilty and were asked to pay back to the peasants. Expecting refusal, they offered to pay only 25 percent of the amount. Gandhi accepted this too because he wanted to free the sharecroppers from the binding of the indigo contract. He opened six schools in Champaran villages and volunteers like Mahadev Desai, Narhari Parikh, and his son, Devdas taught them. Kasturbai, the wife of Gandhi used to teach personal hygiene. Later on, with the help of a volunteer doctor he provided medical facility to the natives of Champaran, thus making their life a bit better. A peace maker, Andrews wanted to volunteer at Champaran ashram. But Gandhi refused as he wanted Indians to learn the lesson of self reliance so that they would not depend on others. Gandhi told the writer that it was Champaran’s incident that made him think that he did not need the Britisher’s advice while he was in his own country.

Indigo text with word meaning

When I first visited Gandhi in 1942 at his ashram in Sevagram, in central India, he said, “I will tell you how it happened that I decided to urge the departure of the British. It was in 1917.”

He had gone to the December 1916 annual convention of the Indian National Congress party in Lucknow. There were 2,301 delegates and many visitors. During the proceedings, Gandhi recounted, “a peasant came up to me looking like any other peasant in India, poor and emaciated, and said, ‘I am Rajkumar Shukla. I am from Champaran, and I want you to come to my district’!’’ Gandhi had never heard of the place. It was in the foothills of the towering Himalayas, near the kingdom of Nepal.

Under an ancient arrangement, the Champaran peasants were sharecroppers. Rajkumar Shukla was one of them. He was illiterate but resolute. He had come to the Congress session to complain about the injustice of the landlord system in Bihar, and somebody had probably said, “Speak to Gandhi.”

Gandhi told Shukla he had an appointment in Cawnpore and was also committed to go to other parts of India. Shukla accompanied him everywhere. Then Gandhi returned to his ashram near Ahmedabad. Shukla followed him to the ashram. For weeks he never left Gandhi’s side. “Fix a date,” he begged.

Impressed by the sharecropper’s tenacity and story Gandhi said, ‘‘I have to be in Calcutta on such-and-such a date. Come and meet me and take me from there.”

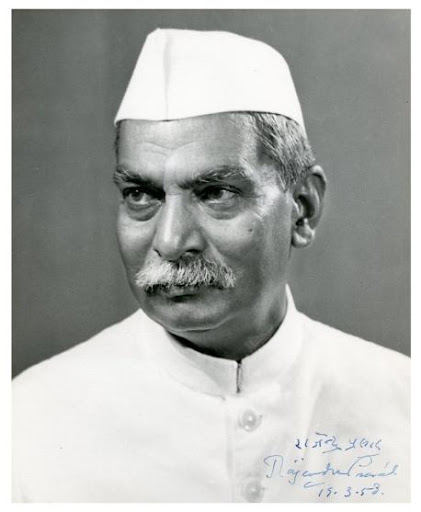

Months passed. Shukla was sitting on his haunches at the appointed spot in Calcutta when Gandhi arrived; he waited till Gandhi was free. Then the two of them boarded a train for the city of Patna in Bihar. There Shukla led him to the house of a lawyer named Rajendra Prasad who later became the President of the Congress party and of India. Rajendra Prasad was out of town, but the servants knew Shukla as a poor yeoman who pestered their master to help the indigo sharecroppers. So they let him stay on the ground with his companion, Gandhi, whom they took to be another peasant. But Gandhi was not permitted to draw water from the well lest some drops from his bucket pollute the entire source; how did they know that he was not an untouchable?

Gandhi decided to go first to Muzaffarpur, which was en route to Champaran, to obtain a more complete information about conditions than Shukla was capable of imparting. He accordingly sent a telegram to Professor J.B. Kripalani, of the Arts College in Muzaffarpur, whom he had seen at Tagore’s Shantiniketan School. The train arrived at midnight, 15 April 1917. Kripalani was waiting at the station with a large body of students. Gandhi stayed there for two days in the home of Professor Malkani, a teacher in a government school.

‘‘It was an extraordinary thing ‘in those days,’’ Gandhi commented, “for a government professor to harbour a man like me”. In smaller localities, the Indians were afraid to show sympathy for advocates of home-rule.

The news of Gandhi’s advent and of the nature of his mission spread quickly through Muzzafarpur and to Champaran. Sharecroppers from Champaran began arriving on foot and by conveyance to see their champion. Muzzafarpur lawyers called on Gandhi to brief him; they frequently represented peasant groups in court; they told him about their cases and reported the size of their fee

Gandhi chided the lawyers for collecting big fee from the sharecroppers. He said, ‘‘I have come to the conclusion that we should stop going to the law courts. Taking such cases to the courts does litte good. Where the peasants are so crushed and fear-stricken, law courts are useless. The real relief for them is to be free from fear.’’

At this point Gandhi arrived in Champaran. He began by trying to get the facts. First he visited the secretary of the British landlord’s association. The secretary told him that they could give no information to an outsider. Gandhi answered that he was no outsider.

Next, Gandhi called on the British official commissioner of the Tirhut division in which the Champaran district lay. ‘‘The commissioner,’’ Gandhi reports, ‘‘proceeded to bully me and advised me forthwith to leave Tirhut.’’

Gandhi did not leave. Instead he proceeded to Motihari, the capital of Champaran. Several lawyers accompanied him. At the railway station, a vast multitude greeted Gandhi. He went to a house and, using it as headquarters, continued his investigations. A report came in that a peasant had been maltreated in a nearby village. Gandhi decided to go and see; the next morning he started out on the back of an elephant. He had not proceeded far when the police superintendent’s messenger overtook him and ordered him to return to town in his carriage. Gandhi complied. The messenger drove Gandhi home where he served him with an official notice to quit Champaran immediately. Gandhi signed a receipt for the notice and wrote on it that he would disobey the order.

In consequence, Gandhi received the summons to appear in court the next day.

All night Gandhi remained awake. He telegraphed Rajendra Prasad to come from Bihar with influential friends. He sent instructions to the ashram. He wired a full report to the Viceroy.

Morning found the town of Motihari black with peasants. They did not know Gandhi’s record in South Africa. They had merely heard that a Mahatma who wanted to help them was in trouble with the authorities. Their spontaneous demonstration, in thousands, around the courthouse was the beginning of their liberation from fear of the British.

The officials felt powerless without Gandhi’s cooperation. He helped them regulate the crowd. He was polite and friendly. He was giving them concrete proof that their might, hitherto dreaded and unquestioned, could be challenged by Indians.

The government was baffled. The prosecutor requested the judge to postpone the trial. Apparently, the authorities wished to consult their superiors.

Gandhi protested against the delay. He read a statement pleading guilty. He was involved, he told the court, in a “conflict of duties”— on the one hand, not to set a bad example as a lawbreaker; on the other hand, to render the “humanitarian and national service” for which he had come. He disregarded the order to leave, “not for want of respect for lawful authority, but in obedience to the higher law of our being, the voice of conscience”. He asked the penalty due.

The magistrate announced that he would pronounce sentence after a two-hour recess and asked Gandhi to furnish bail for those 120 minutes. Gandhi refused. The judge released him without bail.

When the court reconvened, the judge said he would not deliver the judgment for several days. Meanwhile he allowed Gandhi to remain at liberty.

Rajendra Prasad, Brij Kishor Babu, Maulana Mazharul Huq and several other prominent lawyers had arrived from Bihar. They conferred with Gandhi. What would they do if he was sentenced to prison, Gandhi asked. Why, the senior lawyer replied, they had come to advise and help him; if he went to jail there would be nobody to advise and they would go home.

What about the injustice to the sharecroppers, Gandhi demanded. The lawyers withdrew to consult. Rajendra Prasad has recorded the upshot of their consultations — “They thought, amongst themselves, that Gandhi was totally a stranger, and yet he was prepared to go to prison for the sake of the peasants; if they, on the other hand, being not only residents of the adjoining districts but also those who claimed to have served these peasants, should go home, it would be shameful desertion”

They accordingly went back to Gandhi and told him they were ready to follow him into jail. ‘‘The battle of Champaran is won,’’ he exclaimed. Then he took a piece of paper and divided the group into pairs and put down the order in which each pair was to court arrest.

Several days later, Gandhi received a written communication from the magistrate informing him that the Lieutenant-Governor of the province had ordered the case to be dropped.

Civil disobedience had triumphed, the first time in modern India.

Gandhi and the lawyers now proceeded to conduct a far-flung inquiry into the grievances of the farmers. Depositions by about ten thousand peasants were written down, and notes made on other evidence. Documents were collected. The whole area throbbed with the activity of the investigators and the vehement protests of the landlords.

In June, Gandhi was summoned to Sir Edward Gait, the Lieutenant-Governor. Before he went he met leading associates and again laid detailed plans for civil disobedience if he should not return.

Gandhi had four protracted interviews with the Lieutenant- Governor who, as a result, appointed an official commission of inquiry into the indigo sharecroppers’ situation. The commission consisted of landlords, government officials, and Gandhi as the sole representative of the peasants.

Gandhi remained in Champaran for an initial uninterrupted period of seven months and then again for several shorter visits. The visit, undertaken casually on the entreaty of an unlettered peasant in the expectation that it would last a few days, occupied almost a year of Gandhi’s life.

The official inquiry assembled a crushing mountain of evidence against the big planters, and when they saw this they agreed, in principle, to make refunds to the peasants. “But how much must we pay?” they asked Gandhi.

They thought he would demand repayment in full of the money which they had illegally and deceitfully extorted from the sharecroppers. He asked only 50 per cent. “There he seemed adamant,” writes Reverend J. Z. Hodge, a British missionary in Champaran who observed the entire episode at close range. “Thinking probably that he would not give way, the representative of the planters offered to refund to the extent of 25 per cent, and to his amazement Mr. Gandhi took him at his word, thus breaking the deadlock.

Events justified Gandhi’s position. Within a few years the British planters abandoned their estates, which reverted to the peasants. Indigo sharecropping disappeared.

Events justified Gandhi’s position. Within a few years the British planters abandoned their estates, which reverted to the peasants. Indigo sharecropping disappeared.

Health conditions were miserable. Gandhi got a doctor to volunteer his services for six months. Three medicines were available — castor oil, quinine and sulphur ointment. Anybody who showed a coated tongue was given a dose of castor oil; anybody with malaria fever received quinine plus castor oil; anybody with skin eruptions received ointment plus castor oil.

Gandhi noticed the filthy state of women’s clothes. He asked Kasturbai to talk to them about it. One woman took Kasturbai into her hut and said, ‘‘look, there is no box or cupboard here for clothes. The sari I am wearing is the only one I have.”

During his long stay in Champaran, Gandhi kept a long distance watch on the ashram. He sent regular instructions by mail and asked for financial accounts. Once he wrote to the residents that it was time to fill in the old latrine trenches and dig new ones otherwise the old ones would begin to smell bad.

But Champaran did not begin as an act of defiance. It grew out of an attempt to alleviate the distress of large numbers of poor peasants. This was the typical Gandhi pattern — his politics were intertwined with the practical, day-to-day problems of the millions. His was not a loyalty to abstractions; it was a loyalty to living, human beings.

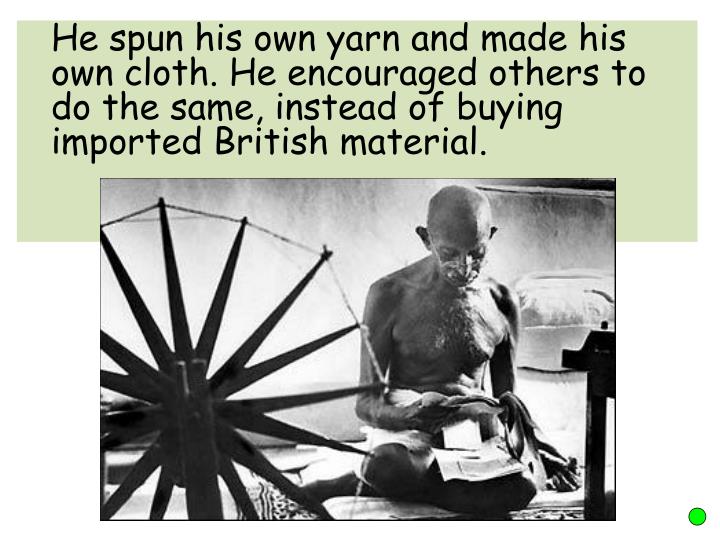

Early in the Champaran action, Charles Freer Andrews, the English pacifist who had become a devoted follower of the Mahatma, came to bid Gandhi farewell before going on a tour of duty to the Fiji Islands. Gandhi’s lawyer friends thought it would be a good idea for Andrews to stay in Champaran and help them. Andrews was willing if Gandhi agreed. But Gandhi was vehemently opposed. He said, ‘‘you think that in this unequal fight it would be helpful if we have an Englishman on our side. This shows the weakness of your heart. The cause is just and you must rely upon yourselves to win the battle. You should not seek a prop in Mr. Andrews because he happens to be an Englishman’’.

Self-reliance, Indian independence and help to sharecroppers were all bound together.

MIND MAP

FLOW CHART FOR CHAPTER

RAJKUMAR SHUKLA (Peasant from Champaran)

↓

Meets Gandhi at Congress Session in Lucknow (1916)

↓

Persistently follows Gandhi → Gandhi agrees to visit Champaran

↓

Gandhi arrives in Champaran (1917)

↓

Learns about:

- Exploitation by British landlords

- 15% land for indigo → rent to landlords

- Compensation disputes after synthetic indigo

↓

Gandhi decides to investigate despite British orders to leave

↓

Gandhi is summoned to court → crowd gathers in support

↓

Gandhi refuses to leave → case dropped

↓

Gandhi and local lawyers gather evidence and testimonies

↓

British authorities set up a commission of inquiry

↓

Landlords agree to refund 25% of money to peasants

↓

Victory for peasants → beginning of their empowerment

↓

Gandhi initiates reforms:

- Education

- Health and hygiene

- Upliftment of villages

↓

Establishment of Gandhi as a national leader

→ Champaran movement = First success of Satyagraha in India

Indigo - Question and Answers

Q1- Why do you think Gandhi considered the Champaran episode to be a turning-point in his life?

Ans- The Champaran event had solved various problems faced by the poor peasants. They were relieved from the torture they had to face at the hands of the landlords. Thousands of people supported him. This was considered as a turning point in the life of Gandhi. He once said that what he did was an ordinary thing as he didn’t want the Britishers to order him in his own country.

Q2- How was Gandhi able to influence lawyers? Give instances.

Ans- Gandhi asked the lawyers about their course of action if he was sentenced to jail. They answered that they would return back. He then asked them about the plight of the peasants. This made them realize their duty towards the social issue and they decided to go to jail with Gandhi.

Q3- What was the attitude of the average Indian in smaller localities towards advocates of ‘home rule’?

Ans- The average Indians in smaller localities did not support the advocates of Home Rule as they feared to go against the British government. For Gandhi it was surprising that Professor Malkani allowed him to stay at his home even though he was a government teacher.

Q4-How do we know that ordinary people too contributed to the freedom movement?

Ans- Ordinary people too contributed to the freedom movement. This can be justified by the following events:

- A large number of students accompanied Prof. J.B Kriplani to welcome Gandhi at Muzzafarpur railway station.

- Peasants also came to see him either on foot or by conveyance.

- A large number of people gathered to demonstrate around the courtroom.

THINK AS YOU READ

Q1. Strike out what is not true in the following:

(a)Rajkumar Shukla was:

(i)a sharecropper (ii)a politician

(iii)delegate (iv)a landlord.

(b) Rajkumar Shukla was:

(i) poor (ii)physically strong

(iii) illiterate.

Ans: (a) (ii) a politician

(b) (ii) physically strong

Q2. Why is Rajkumar Shukla described as being ‘resolute’?

Ans: He had come all the way from Champaran district in the foothills of Himalayas to Lucknow to speak to Gandhi. Shukla accompanied Gandhi everywhere. Shukla followed him to the ashram near Ahmedabad. For weeks he never left Gandhi’s side till Gandhi asked him to meet at Calcutta.

Q3. Why do you think the servants thought Gandhi to be another peasant?

Ans: Shukla led Gandhi to Rajendra Prasad’s house. The servants knew Shukla as a poor yeoman. Gandhi was also clad in a simple dhoti. He was the companion of a peasant. Hence, the servants thought Gandhi to be another peasant.

THINK AS YOU READ

Q1. List the places that Gandhi visited between his first meeting with Shukla and his arrival at Champaran.

Ans: Gandhi’s first meeting with Shukla was at Lucknow. Then he went to Cawnpore and other parts of India. He returned to his ashram near Ahmedabad. Later he went to Calcutta, Patna and Muzaffarpur before arriving at Champaran.

Q2. What did the peasants pay the British landlords as rent? What did the British now want instead and why? What would be the impact of synthetic indigo on the prices of natural indigo?

Ans: The peasants paid the British landlords indigo as rent. Now Germany had developed synthetic indigo. So, the British landlords wanted money as compensation for being released from the 15 per cent arrangement. The prices of natural indigo would go down due to the synthetic Indigo.

THINK AS YOU READ

Q1. The events in this part of the text illustrate Gandhi’s method of working. Can you identify some instances of this method and link them to his ideas of Satyagraha and non-violence?

Ans: Gandhi’s politics was intermingled with the day-to-day problems of the millions of Indians. He opposed unjust laws. He was ready to court arrest for breaking such laws and going to jail. The famous Dandi March to break the ‘salt law’ is another instance. The resistance and disobedience was peaceful and a fight for truth and justice…This was linked directly to his ideas of Satyagraha and non-violence.

THINK AS YOU READ

Q1. Why did Gandhi agree to a settlement of 25 per cent refund to the farmers?

Ans: For Gandhi the amount of the refund was less important than the fact that the landlords had been forced to return part of the money, and with it, part of their prestige too. So, he agreed to settlement of 25 per cent refund to the farmers.

Q2. How did the episode change the plight of the peasants?

Ans: The peasants were saved from spending time and money on court cases. After some years the British planters gave up control of their estates. These now reverted to the peasants. Indigo sharecropping disappeared.

UNDERSTANDING THE TEXT

Q1.Why do you think Gaffdhi considered the Champaran episode to be a turning- point in his life?

Ans: The Champaran episode began as an attempt to ease the sufferings of large number of poor peasants. He got spontaneous support of thousands of people. Gandhi admits that what he had done was a very ordinary thing. He declared that the British could not order him about in his own country. Hence, he considered the Champaran episode as a turning- point in his life.

Q2. How was Gandhi able to influence lawyers? Give instances.

Ans: Gandhi asked the lawyers what they would do if he was sentenced to prison. They said that they had come to advise him. If he went to jail, they would go home. Then Gandhi asked them about the injustice to the sharecroppers. The lawyers held consultations. They came to the conclusion that it would be shameful desertion if they went home. So, they told Gandhi that they were ready to follow him into jail.

Q3. “What was the attitude of the average Indian in smaller localities towards advocates of ‘home rule’?

Ans: The average Indians in smaller localities were afraid to show sympathy for the advocates of home-rule. Gandhi stayed at Muzaffarpur for two days at the home of Professor Malkani, a teacher in a government school. It was an extraordinary thing in those days for a government professor to give shelter to one who opposed the government.

Q4. How do we know that ordinary people too contributed to the freedom movement?

Ans: Professor J.B. Kriplani received Gandhi at Muzaffarpur railway station at midnight. He had a large body of students with him. Sharecroppers from Champaran came on foot and by conveyance to see Gandhi. Muzaffarpur lawyers too called on him. A vast multitude greeted Gandhi when he reached Motihari railway station. Thousands of people demonstrated around the court room. This shows that ordinary people too contributed to the freedom movement in India.

SHORT NOTES ON THE EVENTS OF THE CHAPTER

Gandhiji urged the return of Britishers from India. This movement started

in 1917 when an illiterate peasant, Raj Kumar Shukla approached Gandhiji to ask

him to solve the problem of the poor peasants of Champaran.

v The Champaran Peasants

·

Raj Kumar

Shukla shared with Gandhiji the miseries of the people of Champaran. He termed

the landlord system in Bihar gravely unjust and wanted Gandhiji to help the

poor peasants.

v Shuklas Tenacity, Perisistance, Resolve,

Determination

·

Shukla

visited Gandhiji in Lucknow and then in Cawnpore. He was told that Gandhi was

scheduled to visit other places in the coming days. Shukla patiently followed

him everywhere. Gandhiji agreed to accompany him to Champaran after his

Calcutta visit.

v Rajendra Prasad's House at Patna

·

Gandhiji

wished to meet Rajendra Prasad, a lawyer who later became the president of the

Indian National Congress. But the meeting did not take place as he was out of

town,

·

Gandhiji

then left for Muzzaffarpur to gather more information. Lawyers briefed Gandhiji

on the case and were chided by him for collecting high fees from the peasants.

Gandhiji decided to free the poor farmers from fear.

v Ancient Settlement

·

Large

Indian estates were owned by the Britishers who had put a compulsion on the

Indian tenants to grow indigo in 15% land. Farmers were deprived of the indigo

harvest. The entire indigo produce was taken as rent.

v German Synthetic Indigo

·

Landlords

did not want the indigo produce anymore as the coming of synthetic indigo

reduced natural crop cheap. The landlords released them from ancient agreement

but charged compensation for it. Some peasants signed the agreement willingly,

some engaged lawyers to resist it. When the news of the synthetic indigo reached

the peasants, they wanted their money back.

v Official Notice to Gandhiji

·

Gandhi

was ordered to leave Champaran. He took the order but signed his refusal. He

was summoned to appear in the court the next day. Rajendra Prasad arrived with

influential friends. Peasants came in thousands and the Britishers had to take

Gandhiji's help to regulate the crowd.

v Gandhiji's Reason for Disobedience

·

Gandhiji

disobeyed not to break law but to render humanitarian and national service. He

professed that he did not have any disrespect for law but for greater respect

for the voice of conscience.

v Triumph of Civil Disobedience

·

Gandhiji

proceeded to gather testimonies about grieving farmers. The Lt. Governor

appointed a commission of inquiry comprising landlords, government officials

and Gandhiji as the sole representative of farmers.

v British planters Defeated

·

When

heaps of evidences were collected against landlords, they agreed to refund the

money but only 25% of it. They had assumed that Gandhiji would not come down

from his demand of 50%. Surprisingly Gandhiji agreed to 25% as he believed that

refund did not matter but that the landlords had to surrender their prestige.

This victory of peasants brought courage in them. Later on the estate holders

left their holdings and the land reverted to the peasants.

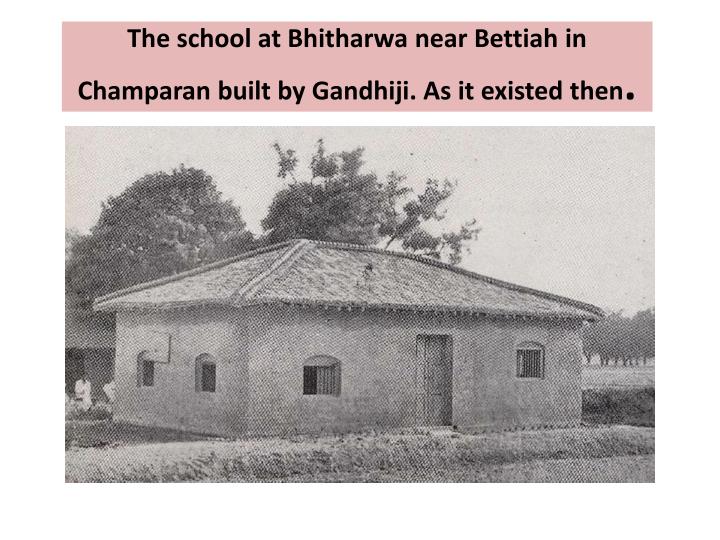

v Social, Cultural upliftment of Champaran

·

To

improve cultural and social lot of the people Gandhiji sought volunteers for

teaching. His own family including wife and son volunteered. Primary Schools

were opened and hygiene and health was taken care of. His politics comprised

day to day problems.

v Chamaparan, a Turning Point

·

Gandhiji

had learnt that he could not be ordered about in his own country.

·

Peasants

had learnt courage and also the fact that he could fight for his rights.

v Self-Reliance

· Charles Freer Andrew's, a pacifist and a devout disciple of Gandhiji came to bid him farewell. The lawyer friends urged him to stay on in Champaran for the support of Indians. But Gandhiji was against the proposal as he wanted the Indians to face the crisis on their own.

EXTRA QUESTIONS WITH ANSWER HINTS

📘 1. Title-Based Question

Q: Why is the chapter titled Indigo?

Hint:

• Symbolic of the oppression faced by Indian peasants.

• Focuses on Champaran’s indigo sharecroppers and their exploitation by British landlords.

• The success of Gandhi’s movement around the indigo issue made it historically significant.

• Indigo = Central to the cause and the first triumph of civil disobedience.

🎯 2. Theme-Based Question

Q: What is the central theme of the chapter Indigo?

Hint:

• Social injustice and freedom from exploitation.

• Use of non-violent protest (Satyagraha) for civil rights.

• Awakening of Indian nationalism.

• Empowerment of the poor through self-reliance and education.

💡 3. Value-Based Question

Q: What values does Gandhi’s handling of the Champaran issue reflect?

Hint:

• Truth and non-violence

• Determination and courage

• Empathy and service to the poor

• Belief in justice through peaceful means

• Leadership through example, not dominance

🧠 4. Competency-Based Question

Q: How did Gandhi’s intervention in Champaran change the outlook of the local peasants and lawyers?

Hint:

• Peasants gained confidence and dignity.

• Lawyers learned the true meaning of service and justice.

• Gandhi’s courage inspired collective resistance.

• Shift from fear to empowerment and unity.

Q: What does Gandhi’s method of solving the Champaran issue tell us about his leadership style?

Hint:

• He led by example, not by command

• Involved local people in decision-making

• Used peaceful tools like persuasion, truth, and unity

• Prioritized long-term reform over temporary victory

Q: How did Gandhi use the legal system to fight injustice in Champaran?

Hint:

• Refused to follow unjust orders

• Accepted arrest, attended court with dignity

• Gathered evidence legally and systematically

• Used truth and transparency to win support

Q: What can students learn from Gandhi’s strategy in resolving the Champaran crisis?

Hint:

• Always stand up for what’s right

• Face challenges with calmness and truth

• Small, peaceful actions can lead to big changes

• Knowledge and courage empower people

🧾 5. Situation-Based Question

Q: If you were one of the Champaran peasants, how would you have responded to Gandhi’s support?

Hint (Sample Answer Structure):

• Gratitude for his courage and leadership.

• Felt inspired to raise voice for my rights.

• Would support the movement non-violently.

• Would help spread awareness among other villagers.

Q: Imagine you are a British official witnessing the massive support Gandhi receives at the courthouse. How would you interpret this situation?

Hint:

• Growing unrest among locals

• Gandhi’s influence over common people

• Fear of revolt or disobedience

• Difficulty in controlling people using fear and authority

Q: Suppose Gandhi had left Champaran as ordered. How might that have changed the course of the movement?

Hint:

• Would weaken the morale of peasants

• Lawyers might not have joined the cause

• British planters would remain unchallenged

• Non-violent resistance would not be established as a method

Q: You are a Champaran farmer just informed that Gandhi has succeeded in getting a 25% refund. Describe your reaction.

Hint:

• Sense of relief, pride, and gratitude

• Beginning of hope and dignity

• Motivation to resist future exploitation

• Realization of collective strength

✍️ 6. Creative Writing Based Questions

a) Diary Entry:

Q: Write a diary entry from the perspective of Rajkumar Shukla after Gandhi agrees to visit Champaran.

Hint:

• Express excitement and hope.

• Mention past struggles in trying to get help.

• Believe that change is finally possible.

Q: Imagine you are one of the lawyers from Bihar who initially hesitated to help Gandhi. Write a diary entry after deciding to support him.

Hint:

• Feel ashamed of initial fear

• Inspired by Gandhi’s courage

• Newfound purpose in standing for justice

• Sense of unity with fellow Indians

b) Speech:

Q: Prepare a short speech on how Indigo teaches us about the power of peaceful protest.

Hint:

• Reference Gandhi’s method.

• Civil disobedience as a tool for justice.

• Real-life change through unity and truth.

• Relevance in today’s world.

Q: Write a speech you would deliver in school on the importance of Indigo in India’s freedom movement.

Hint:

• Begin with context of Champaran

• Mention Gandhi’s peaceful leadership

• Show how ordinary people stood for rights

• Conclude with relevance of justice and truth in modern times

C) Letter Writing.

Q: Write a letter from Gandhi to a fellow freedom fighter describing the significance of the Champaran movement.

Hint:

• Highlight how people gained courage

• Talk about success through non-violence

• Mention the victory of ordinary peasants

• Emphasize self-reliance and truth

D) Report Writing (Newspaper )

Q: Write a newspaper report on Gandhi’s success in Champaran for a local journal.

Hint:

• Use a headline like: “Victory for Peasants in Champaran!”

• Describe the 25% refund decision

• Mention support from locals and lawyers

• Quote Gandhi’s views on truth and justice

📚 7. Other Possible Extra Questions

a) Q: How did the British planters react to Gandhi’s presence in Champaran?

Hint:

• Initially hostile and dismissive.

• Tried legal intimidation.

• Eventually gave in due to public pressure and Gandhi’s calm resistance.

b) Q: Why was the Champaran episode a turning point in Gandhi’s life?

Hint:

• First major civil disobedience movement in India.

• Marked Gandhi’s transition to a national leader.

• Showed the effectiveness of non-violent methods.

c) Q: What role did education and social reform play in Gandhi’s approach in Champaran?

Hint:

• Started schools, improved sanitation.

• Believed that freedom also means development and dignity.

• Empowerment through literacy, awareness, and hygiene.

Comments

Post a Comment